|

By Eva True (They/Them) (Representative)

It’s that time of year again. Pride Month is when we all come together to celebrate the LGBTQ+ community and its shameless existence in the face of seemingly insurmountable adversity. We at LGBTQ+ of FIRST strive to “do justice” to this occasion in a variety of ways. Namely, these ways include blog posts, social media content, and Discord events. I usually volunteer to write a blog post or two for the org during every pride month. This year’s theme was… difficult to come up with, to say the least. I’ve been sitting at my desk staring at a blank Word document and past blog posts on the website for the better part of an hour. A lot of the actionable advice, agendas, and personal testimonials have been written and rewritten over the years. That’s when it hit me. We look to the present and future a lot in our content, but have we ever really dug into the past? FIRST, at its very core, is a microcosm of what you see in the STEM world. For decades, that meant straight men being the dominant demographic. It also meant that breaking that “mold” was frowned upon and discouraged in a variety of ways. Andy Baker has occasionally appeared at LGBTQ+ of FIRST roundtables to discuss what it meant to be queer in the STEM landscape before some relatively recent changes. After a few conversations with Jon Kentfield, who’s been involved with FIRST since the early 2000s, FIRST was one of the more accepting spaces to hang around in the 90s and 2000s. However, in the age of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” being both a legislative and societal norm until the 2010s, only so much could really be done. My understanding was that being ‘out’ to a limited number of people was safer within FIRST than it was within the broader world. On top of that, a central teaching of FIRST has always been to accept others, regardless of their differences. I don’t doubt that the program was at least a limited haven for queer people in the STEM community. Now, let’s get to the details most of us were alive to witness. It’s 2015, Obergefell v. Hodges is found in favor of the plaintiff and gay marriage becomes federally legal. Conversations are being had that weren’t necessarily even thought about in the 90s and 2000s. Society is changing, rapidly. At this time, queer communities verifiably existed within FIRST in a number I wasn’t able to confirm. Within the year, what would eventually become LGBTQ+ of FIRST began as a Tumblr page. The details on this are shaky and I don’t have a primary source at hand to ask, but some digging shows that the Discord server came to be in the spring of 2016. Things were slowly changing, of course. However, I’d like to cite a 2022 interview I conducted with Jon Kentfield. He said that he didn’t notice a major shift until after LGBTQ+ of FIRST gained momentum across the United States, and eventually, the world. In the following years, changes began to sweep through the program rapidly. 2018 marked the first LGBTQ+ of FIRST conference in Detroit. It was also the first year Woodie Flowers was publicly seen wearing an LGBTQ+ of FIRST enamel pin. This started an interesting trend where you’d see all the most visible people within the program, such as Blair Hundertmark and Frank Merrick, sporting the pins. This visibility was vital for growing the org. One annual conference quickly turned into a handful of roundtables, and then an entire calendar of events becoming a regular part of FIRST events. In Indiana, 6956 Sham-Rock-Botics played a leading role in making the district more inclusive. In 2024, the events are adorned with pride flags supplied by their team, and LGBTQ+ of FIRST roundtables are held at 2 FRC district events and at DCMP. The physical presence is nearly universal, at least within the United States and Canada. This presence can manifest as partner teams or staff members, but it never seems to take longer than 5 minutes to find somebody willing to hand you a pin, a pamphlet, and tell you about the organization. The Rainbow STEM Alliance was formed to manage this growth and serve as a financial “shell” for the organization. This was explosive for LGBTQ+ of FIRST, enabling the two organizations to work together on partnerships, finances, material distribution, and even an entire offseason event held annually. In the online world, the server now has over 1,300 members. The staff maintains an active blog and social media presence. We even collaborate with FIRST and entities such as FUN regularly on content relating to the work we do. Other communities, such as Neurodivergent of FIRST and Disabled People of FIRST owe their existence to the path that LGBTQ+ of FIRST paved in the late 2010s. I can tell you that I heard about the organization in passing in 2018. The only way to receive a pin was directly from one of a handful of staff members. In the 6 years since, I cannot express how glad I am to see the entire FIRST community embracing equality and inclusion for everyone. This leaves one clear message to queer people in the program: “You are welcome here”. Last week was trans awareness week, a week dedicated to bringing awareness to transgender people internationally and the struggles they face. The final day (November 20th) was trans remembrance day, a day dedicated to remembering victims of transphobic violence. Transgender awareness week was created in 1999 by Gwendolyn Ann Smith in honor of Rita Hester, a transgender woman who was murdered in 1998. Ever since then we take the day of November 20th to mourn those lost to violence and hate crimes due to nothing more than living their truest lives.

Trans awareness week holds many different values to different members of the community. For many, this is a day of celebration, a week for gender-nonconforming people from around the world to celebrate their identity and all that has been accomplished for the transgender community. For others, it is a time of mourning for friends, family, and community members lost. For those who celebrate it is shown by parades, parties, and events held by local community members. All around just working to make themselves visible and show that they are proud of who they are. It is also used as a time to educate the public on transgender rights and gender-nonconforming identities. There are programs run across the country to educate on everything from sex ed to advocacy for trans students. As issues with transgender students especially when it comes to sports arise, the importance of these celebrations and attempts to bring awareness are all that much more important. As young people grow more confident and comfortable with their identities in the newer generations anti-trans hate groups have also grown. These groups work to dispute the validity of transgender identities and cause harm in the community. Now you may be wondering, what can I, a mentor, a student, a friend, or a teacher do to make transgender students feel safer? Luckily there's a lot you can do! Some important things are making sure your students or friends know you are a safe space and support them. Another thing is to provide gender-neutral bathrooms and spaces for all students. For many students in FIRST, travel rooming is also a concern so it is important to have open honest conversations with your team to ensure everyone feels safe and comfortable. Few words carry as much power as the words we use to describe ourselves. Finding a label that fits your experiences lends a sense of completeness, of accomplishment; it allows you to join a community of others who describe themselves the same way. Many of these words, however, carry more meaning than just a definition.

The word “queer” and its use in the LGBTQ+ community have been a point of contention for much of our history. Today, though many agree that the efforts to publicize LGBTQ+ issues and the concurrent strive for equality has led to the reclamation of the word, it is still often seen – and used – as a slur. To understand this debate, and to informedly take a side, it is important to first understand its history. The origins of the word “queer” have, to a degree, been lost to history. It may have come from a Scottish or German word meaning ‘oblique’ or ‘off-center’, but linguists are uncertain. In any case, by the early 1800s, it had garnered a strongly negative connotation in English – to queer meant to spoil or ruin a situation. The first recorded use of “queer” as a homophobic slur was in 1894, by John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry, who blamed the death of his son Francis on Francis’s suspected love interest, Lord Rosebery. Queensberry, in a letter to another son, speculated that “snob queers like Rosebery” had corrupted his son and led to his demise. During the 1900s, people both inside and outside of the community tended to use “queer” pejoratively, with the slur gaining popularity in the 1950s and later. In 1970, linguist Julia Penelope wrote for the journal American Speech that, in her interviews with gays and lesbians, they all felt that the term “was only used by heterosexuals to express their disdain for homosexuals”. As it is today, bullying of LGBTQ+ students was a massively pervasive issue, and many older members of the community today dislike the word “queer” because they most often heard it as a targeted attack on their identity. Some LGBTQ+ activists did embrace the term as a self-identifier: Gertrude Stein, in her 1903 coming-out story Q.E.D., referred to two female love interests as queer. Still, the term remained hateful in mainstream culture until the latter half of the century. The reclamation of the term “queer” trailed after the rise of the mainstream gay rights movement. The term “queercore” emerged in the 80s, sparked by punk zine J.D.s. The publication was launched in 1985 to give a voice to the unruly, anti-establishment wing of the gay rights movement. As cofounder Bruce LaBruce explained, “Gay assimilation was already starting back then, accelerated by the AIDS crisis, so the gay movement was already distancing and disassociating itself from its more unruly, extreme and anti-establishment elements – queers who did not fit into the gay white bourgeois patriarchy.” Queercore music gave voice to LGBTQ+ artists who were tired of societal disapproval, and allowed them to express their outrage through the time-honored outlet of punk music. More radical efforts to reclaim “queer” began in the 1990s. Queer Nation, founded in 1990, is a New York-based LGBTQ+ activist organization. Founded by members of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) who were outraged about the escalation of violence against a community still grieving and suffering from the AIDS epidemic, Queer Nation strove to educate the public and protest for the promotion of gay rights. They popularized the chant “We’re here! We’re Queer! Get used to it!”, which became a rallying cry for the community. They also distributed leaflets with titles like “We’re here, we’re queer, and we’d like to say hello!” and “Queers read this – The Queer Nation Manifesto”, spreading information and safe-sex tips, as well as urging LGBTQ+ people to fight for their rights. Their manifesto actively pushed for use of the word “queer” to describe themselves: “Well, yes, ‘gay’ is great. It has its place. But when a lot of lesbians and gay men wake up in the morning we feel angry and disgusted, not gay. So we’ve chosen to call ourselves queer”. Today, “queer” is often used as a catchall term for members of the LGBTQ+ community. For people whose sexuality or gender identity is uncertain or difficult to explain, “queer” is also valued as a concise way to explain how they identify. Still, the word’s history casts a shadow over its use today: on its website, PFLAG advises that, due to its history as a slur, the word “queer” “should only be used when self-identifying or quoting someone who self-identifies as queer”. -- For many LGBTQ+ students, their FIRST team feels like a safe place to come out. The sense of camaraderie, of family, lets them comfortably be who they are and express their identity. Coming out is an extremely important event in the lives of many LGBTQ+ people, and finding a label that describes one’s identity carries just as much weight. On FIRST teams, surrounded by young people who have, for the most part, seen “queer” as a fairly mainstream identifier of sexuality, some may find solace in a label that cements their place in the LGBTQ+ community, but doesn’t hold them to strict standards or stereotypes, and accepts uncertainty or vagueness about the precise nature of their identity. Still, the word’s history cannot be ignored. When I was younger, my dad gave me one of the most valuable pieces of advice I’ve ever received. “Words are just words,” he said, “until you give them meaning.” Though the word “queer” has a controversial history, its meaning today is, simply put, what you make of it. For some, it’s a word we use to describe our identities. For others, it’s a curse spat with hatred and ignorance. Personally, I believe that my queer brothers and sisters have spent decades fighting for our right to describe ourselves however we like, to truly embrace what makes us unique, to take our places in a community that understands not only our struggles, but also our joy, our passion, and our love. I am queer, and I’m proud to say it. But it’s up to you. -Tess M. Not so long ago, and for the first time, I watched the classic documentary The Times of Harvey Milk, about the first openly gay individual in California elected to public office.

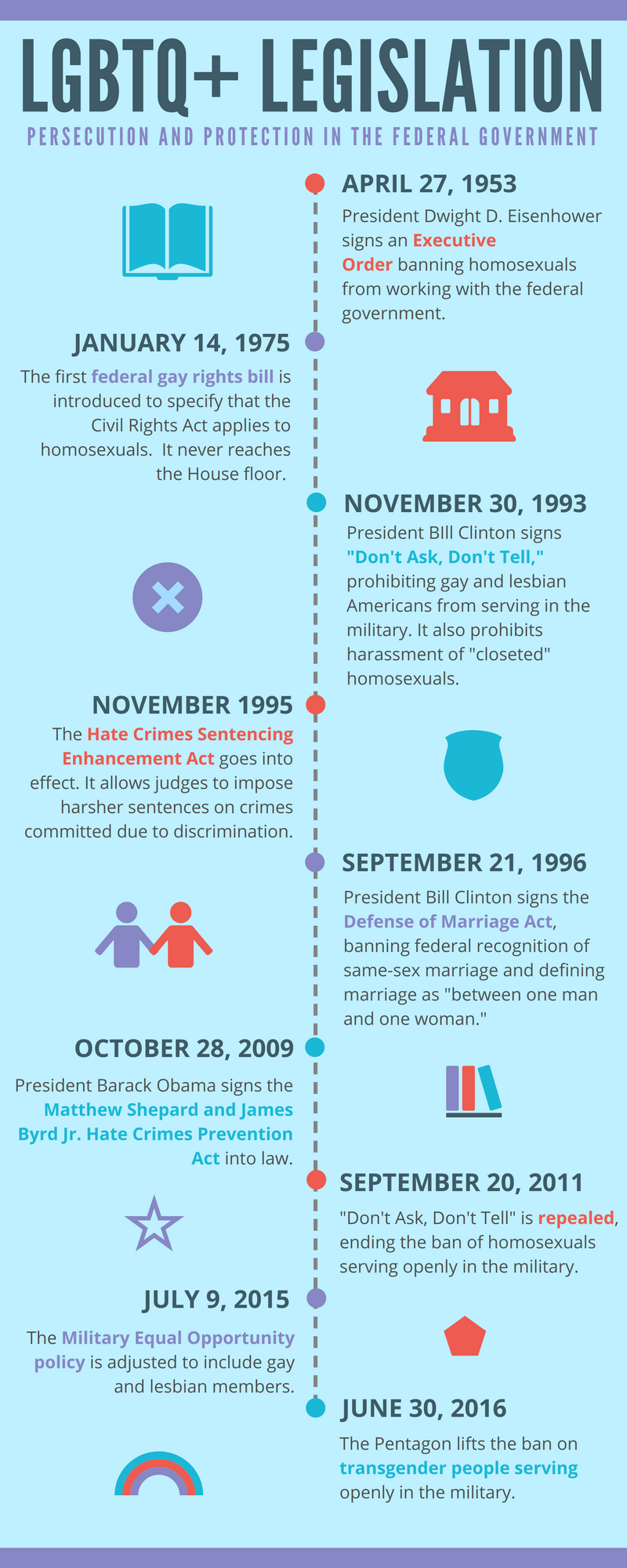

Harvey was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors on November 8, 1977. On November 27, 1978, at San Francisco City Hall, along with George Moscone, the Mayor of San Francisco, Harvey Milk was assassinated. The killer, Dan White, a former colleague of Harvey’s on the Board of Supervisors who had resigned his post just weeks before, was tried for capital murder. This could have earned him the death penalty. Instead, he was found guilty of manslaughter and served 5 years of a 7-year sentence before being paroled. Approximately 1 year and 10 months after his parole, Dan White committed suicide. What struck me about this film was not just the incredible story and the apparent injustice in the sentencing of Dan White, but the representation of what our culture was like at the time. California Proposition 6, also known as ‘The Briggs Initiative’ after its sponsor, John Briggs, was on the ballot in the November 1978 election. The language of the proposition, though convoluted, would have essentially prohibited the hiring of, and required the firing of, public school teachers for “public homosexual conduct”, a term defined so broadly that I think it would be hard for any homosexual, or even any what today might be called heterosexual ally, to not fall under the law’s purview. Here’s the thing, for me: this proposition, clearly discriminatory and unjust by today’s standards, nearly passed. In September of 1978, only two months before voting, polling showed it ahead. It was only through the extraordinary and determined efforts of Harvey Milk and a broad coalition of others opposed to the proposition, including then-Governor of California Ronald Regan, that it went down in defeat, with 58% voting against. I’ll admit that at least until I watched this extraordinary documentary, I was nearly wholly ignorant of the history of the LGBTQ+ movement. When I realized events such as this happened in my lifetime – I was 13 when the assassinations occurred – my eyes were opened just a bit more. If you haven’t seen The Times of Harvey Milk, even if you already know the story, I believe it’s worth a watch, and worth sharing your thoughts over. It’s powerful filmmaking in the service of an important part of history, history not just for the LGBTQ+ community, but for all. The United States government has had a tormentalous history regarding LGBTQ+ people over the past sixty-five years. From persecution to protection, legislation affecting LGBTQ+ people has changed drastically, from banning homosexuals in the government to protecting them.

On April 27, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450. Stating “any criminal, infamous, dishonest, immoral, or notoriously disgraceful conduct, habitual use of intoxicants to excess, drug addiction, or sexual perversion,” it was broadly interpreted and used to effectively ban gays and lesbians from the federal workforce. It wasn’t until the 1990’s when this order was lifted fully. The U.S. Civil Service Commission re-allowed gays and lesbians in federal civil service in 1975, while in 1977, the state department lifted a ban on gays in the Foreign Service. President Bill Clinton’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy allowed lesbians and gays a place once more in the military in 1995. Bella Abzug introduced a bill to Add Sexual Orientation to Federal Civil Rights Law on January 14, 1975. It was the first federal lesbian and gay rights bill in the federal government, and intended to apply the Civil Rights Act of 1965 to protect sexual orientation. It never reached the house floor. Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, signed into law November 30, 1993 by Bill Clinton, prohibited the military from discriminating against closeted homosexual or bisexual service members. However, openly homosexual or bisexual people were banned completely from military service reasoning that “would create an unacceptable risk to the high standards of morale, good order and discipline, and unit cohesion that are the essence of military capability.” Members who spoke about homosexual relations could be rapidly discharged. In November 1995, the Hate Crimes Sentencing Enhancement Act is added and enacted as an amendment to the Violent Crime and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. Passed by the 103rd Congress, it allowed harsher penalties for hate crimes, especially those based on disability, gender, and sexual orientation and which occurred on federal property. The Defense of Marriage Act, signed November 21, 1996, defined marriage as between a man and a woman in regards to federal law. It allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages officiated in other states or countries, and effectively banned same-sex partnerships from receiving federal marriage benefits awarded to heterosexual couples. Section 3 specified non-recognition of same-sex marriages in federal government, immigration, bankruptcy, joint tax returns, social security survivors’ benefits, certain federal protections, financial aid eligibility, and ethics laws. President Obama’s administration brought forth the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act on October 28, 2009, which expanded a 1969 federal hate crime law to include gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability based motivation. It removed requirements such as victims having involvement in federal activities such as voting, and allowed federal authorities to pursue hate crimes investigations that localities had abandoned. Furthermore, it provided funding to help state and local agencies investigate hate crimes, and required the FBI to track gender and gender identity based hate crime statistics. In December 2010, the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act which banned openly gay, bisexual, and lesbian members from service. It went into effect on September 20, 2011 after an extended period of preparation, as Pentagon and military leaders were reluctant to lift the ban while in the midst of war. The Pentagon also trained over 1.9 million of the 2.2 million military members on proper conduct around their fellow gay, bisexual, and lesbian servicepeople. Additionally, the military began to look into giving same-sex couples limited health, housing, and legal benefits. The Military Equal Opportunity Policy was updated to include gay and lesbian servicemembers on July 9, 2015, as revealed by Defense Secretary Ash Carter. It “ensures that the department, like the rest of the federal government, treats sexual-orientation-based discrimination the same way it treats discrimination based on race, religion, color, sex, age and national origin.” On June 30, 2016, Defense Secretary Ash Carter announced that the Pentagon had lifted the ban on transgender service members. Estimations range from affecting about 0.1% of the 2 million member military, or about 2000 service members to over 12000 members. Full implementation is expected by July 1, 2017. Sources: x x x x x x x x x |

About LGBTQ+ of FIRST

LGBTQ+ of FIRST is a student run organization that advocates awareness and acceptance of LGBTQ+ students, mentors, and volunteers of FIRST Robotics. LGBTQ+ of FIRST reaches out to over 1000 members across the FIRST regions and fronts multiple outreach endeavors. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed