|

By Eva True (They/Them) (Representative)

It’s that time of year again. Pride Month is when we all come together to celebrate the LGBTQ+ community and its shameless existence in the face of seemingly insurmountable adversity. We at LGBTQ+ of FIRST strive to “do justice” to this occasion in a variety of ways. Namely, these ways include blog posts, social media content, and Discord events. I usually volunteer to write a blog post or two for the org during every pride month. This year’s theme was… difficult to come up with, to say the least. I’ve been sitting at my desk staring at a blank Word document and past blog posts on the website for the better part of an hour. A lot of the actionable advice, agendas, and personal testimonials have been written and rewritten over the years. That’s when it hit me. We look to the present and future a lot in our content, but have we ever really dug into the past? FIRST, at its very core, is a microcosm of what you see in the STEM world. For decades, that meant straight men being the dominant demographic. It also meant that breaking that “mold” was frowned upon and discouraged in a variety of ways. Andy Baker has occasionally appeared at LGBTQ+ of FIRST roundtables to discuss what it meant to be queer in the STEM landscape before some relatively recent changes. After a few conversations with Jon Kentfield, who’s been involved with FIRST since the early 2000s, FIRST was one of the more accepting spaces to hang around in the 90s and 2000s. However, in the age of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” being both a legislative and societal norm until the 2010s, only so much could really be done. My understanding was that being ‘out’ to a limited number of people was safer within FIRST than it was within the broader world. On top of that, a central teaching of FIRST has always been to accept others, regardless of their differences. I don’t doubt that the program was at least a limited haven for queer people in the STEM community. Now, let’s get to the details most of us were alive to witness. It’s 2015, Obergefell v. Hodges is found in favor of the plaintiff and gay marriage becomes federally legal. Conversations are being had that weren’t necessarily even thought about in the 90s and 2000s. Society is changing, rapidly. At this time, queer communities verifiably existed within FIRST in a number I wasn’t able to confirm. Within the year, what would eventually become LGBTQ+ of FIRST began as a Tumblr page. The details on this are shaky and I don’t have a primary source at hand to ask, but some digging shows that the Discord server came to be in the spring of 2016. Things were slowly changing, of course. However, I’d like to cite a 2022 interview I conducted with Jon Kentfield. He said that he didn’t notice a major shift until after LGBTQ+ of FIRST gained momentum across the United States, and eventually, the world. In the following years, changes began to sweep through the program rapidly. 2018 marked the first LGBTQ+ of FIRST conference in Detroit. It was also the first year Woodie Flowers was publicly seen wearing an LGBTQ+ of FIRST enamel pin. This started an interesting trend where you’d see all the most visible people within the program, such as Blair Hundertmark and Frank Merrick, sporting the pins. This visibility was vital for growing the org. One annual conference quickly turned into a handful of roundtables, and then an entire calendar of events becoming a regular part of FIRST events. In Indiana, 6956 Sham-Rock-Botics played a leading role in making the district more inclusive. In 2024, the events are adorned with pride flags supplied by their team, and LGBTQ+ of FIRST roundtables are held at 2 FRC district events and at DCMP. The physical presence is nearly universal, at least within the United States and Canada. This presence can manifest as partner teams or staff members, but it never seems to take longer than 5 minutes to find somebody willing to hand you a pin, a pamphlet, and tell you about the organization. The Rainbow STEM Alliance was formed to manage this growth and serve as a financial “shell” for the organization. This was explosive for LGBTQ+ of FIRST, enabling the two organizations to work together on partnerships, finances, material distribution, and even an entire offseason event held annually. In the online world, the server now has over 1,300 members. The staff maintains an active blog and social media presence. We even collaborate with FIRST and entities such as FUN regularly on content relating to the work we do. Other communities, such as Neurodivergent of FIRST and Disabled People of FIRST owe their existence to the path that LGBTQ+ of FIRST paved in the late 2010s. I can tell you that I heard about the organization in passing in 2018. The only way to receive a pin was directly from one of a handful of staff members. In the 6 years since, I cannot express how glad I am to see the entire FIRST community embracing equality and inclusion for everyone. This leaves one clear message to queer people in the program: “You are welcome here”. Last week was trans awareness week, a week dedicated to bringing awareness to transgender people internationally and the struggles they face. The final day (November 20th) was trans remembrance day, a day dedicated to remembering victims of transphobic violence. Transgender awareness week was created in 1999 by Gwendolyn Ann Smith in honor of Rita Hester, a transgender woman who was murdered in 1998. Ever since then we take the day of November 20th to mourn those lost to violence and hate crimes due to nothing more than living their truest lives.

Trans awareness week holds many different values to different members of the community. For many, this is a day of celebration, a week for gender-nonconforming people from around the world to celebrate their identity and all that has been accomplished for the transgender community. For others, it is a time of mourning for friends, family, and community members lost. For those who celebrate it is shown by parades, parties, and events held by local community members. All around just working to make themselves visible and show that they are proud of who they are. It is also used as a time to educate the public on transgender rights and gender-nonconforming identities. There are programs run across the country to educate on everything from sex ed to advocacy for trans students. As issues with transgender students especially when it comes to sports arise, the importance of these celebrations and attempts to bring awareness are all that much more important. As young people grow more confident and comfortable with their identities in the newer generations anti-trans hate groups have also grown. These groups work to dispute the validity of transgender identities and cause harm in the community. Now you may be wondering, what can I, a mentor, a student, a friend, or a teacher do to make transgender students feel safer? Luckily there's a lot you can do! Some important things are making sure your students or friends know you are a safe space and support them. Another thing is to provide gender-neutral bathrooms and spaces for all students. For many students in FIRST, travel rooming is also a concern so it is important to have open honest conversations with your team to ensure everyone feels safe and comfortable. Hello everyone! First of all, happy Transgender Day of Visibility! I have not been a member of LGBTQ+ of FIRST for very long, but we are a very fun and accepting community. Today, being trans day of visibility, I and people everywhere are coming out and being visible. This day is wonderful because we are raising awareness and showing that there are strong, confident, and wonderful trans people all over the world in every skill and profession. I am so proud of every single one of you, closeted or out, questioning or positive, whoever you are. I am proud of you! You are strong! I would like to give a loud proud shoutout to all of the wonderful, smart transgender people of FIRST! You are all amazing people, you are very smart, and you are what makes FIRST, FIRST!

- Nia Ambassador, LGBTQ+ of FIRST The first Pride parade was in 1970, in the beginning of the Gay Liberation Movement and following the Stonewall Riots. At the time, the opposition to allowing LGBTQ+ people to coexist with the general population was contentious: many LGBTQ+ people lived in “gay villages” or “gay ghettos,” with little opportunity and significant violence. The Pride parade was a statement that we’re a part of this world too and that we won’t be swept to the side. The well-known chant “We’re here, we’re queer” is a political statement, making it clear that we do not intend to be brushed away into ghettos or to leave behind who we are. There are thousands of us, walking down your streets, our streets, being who we are, and we’re not leaving. Despite the threats and legal assaults, the Gay Liberation Movement pushed through and made its message loud and clear.

Fifty years since the Stonewall Riots, Pride looks a bit different than it originally did. Today, your average Pride parade is a time for celebration and includes city officials, companies, and the general public. There’s certainly a lot to celebrate. Over the last fifty years, dozens of countries have legalized same-sex relationships and begun to treat LGBTQ+ people as they would any other citizen. The road there was not easy and is not over, but Pride is when we look back and show pride in our accomplishments. It is also to show pride in who we are. Due to things like a general lack of acceptance, the stigma on standing out in this way, and the difficulties homophobia and transphobia has caused people in their lives, it’s easy to be ashamed or embarrassed to be a part of this community. However, it should be even easier to say that it’s a part of who you are and to be proud of it, just as you would for any other aspect of yourself. Going to Pride means seeing thousands of people celebrating what others would shun, making it just a bit easier to say that it’s something you’re proud. For me, going to Pride meant not feeling like the odd one out for the first time. I was free to feel good about myself without feeling the slightest judgment or strangeness, which is really something everyone deserves to feel. Despite the progress, things aren’t perfect now. Pride parades often are accompanied with protestors denouncing what they consider wrong or immoral. Even worse, Pride isn’t always a safe place to be, especially surrounding the parade. Just this year, we’ve had to deal with Nazis and active shooter scares. That same violence that the 1970s movement protested still exists today, intimidating and harming people simply celebrating who they are. Whether in 1970 or 2019, the Pride Parade has the same message: we’re here, we’re queer, and we’re not leaving. And that’s something to be proud of. Ah, Pride month is here. I know this because Target and Macy’s both have their displays of requisite rainbow clothing, a garment to wear that says, “look at me! I’m-“ I’m what, exactly? Gay? Queer? Something on a spectrum to be labeled? And why is this month different than other months?

Pride Month, like many things in culture and history, is complicated. Its history is a wonderful mix of defiance, joy, sadness, and most certainly, passion. To me, Pride Month is a celebration of who we are, a reminder of where we’ve been, a protest against injustices, and a joyous hope for a better world to come. As a celebration, Pride month allows us all to be who we are, in whatever form that takes. My name is Tom, I use he/him pronouns, and I identify as Bi. A few months ago, I was at a performance of the Philadelphia Gay Men’s Chorus. One of the men had a service dog, and during the question and answer period a high schooler asked “whose dog was it?” The gentleman shared an answer I will not soon forget. He said that the service dog was a promise to his longtime partner who died from AIDS. He would continue to use his voice to make a difference in this world, fighting for equality and rights. Not that long ago, being gay meant not having the same rights as others, with the very real possibility of being arrested. Newsweek summarized the complex history of Pride here: https://www.newsweek.com/pride-month-2019-stonewall-50th-anniversary-history-lgbtq-america-history-1440491. Sophia Waterfield writes, “You have to understand that in the 1950s all U.S. states had laws criminalizing same-sex sexual behavior. You could be arrested and even imprisoned for even proposition[ing] someone for sex in public. Lesbians and gay men were routinely fired from their jobs if their boss or coworkers discovered their sexual orientation. “The laws criminalizing same-sex activity gradually disappeared from state penal codes over the years but the U.S. Supreme Court only called them unconstitutional in 2003 in Lawrence v. Texas.” I find it amazing that the current generation of youth are so accepting of others’ sexual and gender identities. Is the world at 100% acceptance? I would be naive to say yes. But it’s far better than even a decade or two ago, which is great progress. Each Pride event is an opportunity to demand acceptance, to demand the same basic rights as any others - human rights. The right to exist, the right to be free in one’s actions, the right to love, the right to body autonomy, the right to dance - every right that is afforded to heterosexual, cisgender people should be applied in the same positive manner to everyone on the gender and sexuality spectrums. Pride reminds us what the best in all of us can be - welcoming, inclusive, and, well, proud. I love being a part of this wonderful community of LGBTQ+, but there are times where I feel I don’t belong. I sometimes wonder, “am I ‘gay’ enough to be a part of a conversation?” Because I have done some things and not others, do those things make me less of an LGBTQ+ person? As I look back at the history of Pride, and where we are today, seeing the amazing people who are so welcoming into the LGBTQ+ group, I can answer my own question - if you identify in any way or part of this group, then you are a part of this amazing band of humanity. So, here I am with this message to you. Pride month is just that - a moment to let yourself be proud. Be proud of who you are. Be proud of where we’ve come as a group. Be proud of where we’re going. I may even buy something rainbow this year. Happy Trans Day of Visibility to the FIRST community! The International Transgender Day of Visibility is an annual holiday celebrated around the world on March 31st. The day is dedicated to celebrating transgender, nonbinary and gender non-conforming people and their accomplishments, as well as bringing attention to the struggles these communities are still facing.

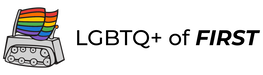

Visibility can be a funny thing to navigate as a trans person. Some trans people may not have a choice in being ‘visibly’ trans, some may choose to be more open about being trans, and others consider their trans experience very private. As someone who went through FIRST programs when closeted and feeling as if I might be the only trans person in FIRST, to now, choosing to be selective about who or what communities know I am trans, I can attest to having many choices to make concerning my visibility as a trans individual. For all my trans brothers, sisters, and siblings, there is no wrong path to take when it comes to your own visibility. You may want to tell everyone you’re trans, or you may be at or want to be at a point where you never tell anyone else. You may also, like many transgender people, be somewhere in the middle, or still at a point where you haven’t told anyone. However you feel most comfortable, most authentic, or are safest is the correct choice. There is nobody who can tell you how much visibility is the correct choice. If you are a cis ally to trans people, it is important for you to respect trans people’s privacy. If a trans person tells you they are trans or you knew someone before they transitioned, don’t share with others unless you have been instructed otherwise. Even if you get questions directly about whether someone is transgender or ‘a boy or a girl.’ If you’re not sure how they would want you to answer those questions, ask when or if they come out to you or politely in a private format. Whether you are a trans person looking for community or a cis person looking to be a good ally, realize that being transgender is not something you can always see. There are trans students on FIRST teams all over the world and in all four FIRST programs, there are trans mentors and coaches working with FIRST teams, there are trans volunteers at many FIRST events in many different roles. There are trans family members- parents, siblings, even grandparents- attending FIRST events in the stands. Trans people are in FIRST, are supporting FIRST, and are an important part of the FIRST community, no matter how visible we might be. Take the opportunity today to learn more about HIV/AIDs, it’s effects, and what is being done now to combat it – and help the people who live with it!

Recently, an admin from LGBTQ+ of FIRST interviewed Tim’m West about LGBTQ+ representation and education in schools. Here’s what he had to say:

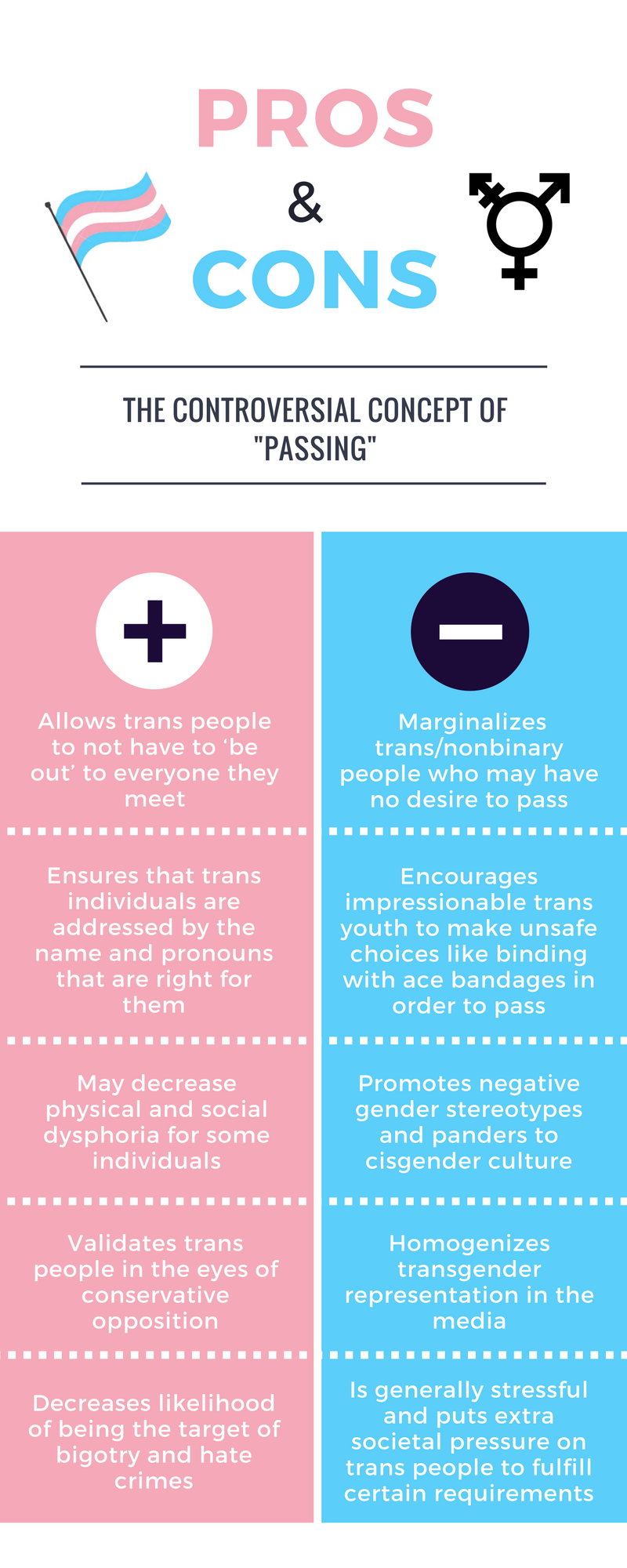

Please give a short introduction for people who may not know you. My name is Tim’m West; professionally and formally I lead Teach For America’s LGBTQ Community initiative. I am a longtime educator, youth advocate, and on the side I do some poetry and hip hop. What brought you to LGBTQ+ activism? I think namely my own personal experience. I grew up a queer kid in the 80’s in southwest Arkansas, and, for me, there weren’t positive queer role models. The only mentions of LGBTQ were negative. For me, the dearth of mirrors to see myself, the absence of LGBTQ people made a difference in how I saw myself. It made me want to teach. I felt that as a teacher I could contribute to making schools a space where students did see you and see that a black queer accomplished man existed and feel you are pretty awesome for that truth. Beyond teaching, that was really important work to do where representation is concerned. I went to school to study philosophy. I thought I would be a college professor, but I ended up leaving my PhD program, and I had two Masters degrees in rather obscure humanities areas, if at good institutions (The New School, Stanford). I got a job running an English department in a high school, so I fell into teaching youth and supporting their academic and social emotional development. Being around youth and understanding their challenges encouraged me to be a better example for them by bringing myself more fully into educational spaces. I have done that in schools as a man who is queer, and I have done that in schools as a man who is HIV positive, which sometimes leads to pushback like, “ooh students don’t need to know that about your personal life”. Still, I’ve taught in places that have high HIV incidence and prevalence. I’d be remiss not to share my own personal experience with them as a way of motivating sexual and emotional safety. What do you see as being the value of LGBTQ+ representation in schools in terms of the teachers? There’s been a lot of data [on the effects of representation], though not a lot of it has been done on the LGBTQ community. For example, in the African American community—and I can say this as an African American who had maybe one African American male teacher in all my schooling—it affected me to not seeing myself represented among the people who are teaching. There have been recent studies that show that students who see themselves represented do better. It’s connected to the reality that less than 2% of teachers in the US are African American men. Yet we know the representation of black boys in public schools is far higher. It actually just creates a situation where people who might be able to best connect and reach students aren’t present. Ultimately, it’s not to say a student can’t learn from anybody, but I think identity and how people see themselves is shaped by those who teach them. So if you’re LGBTQ and you don’t see any teachers or administrators identify that way, it sends a message, an implicit message that you LGBTQ people don’t belong in the places entrusted with our learning; or that if they exist in that space, they’d better be quiet about it. I think connotes a problematic idea of shame; that being LGBTQ is not something that you should be proud of. Being out as a queer teacher is not about the material being any different. What harm is there in knowing that a science or history teacher might be LGBTQ just as we know or assume our teachers are straight? One’s orientation might actually inform something unique about their approaches to teaching or world view. I think that’s important for students to see and experience. How can LGBTQ+ lessons be integrated into the classroom? I have an interesting belief in this, because I don’t believe that LGBTQ issues should be brought into the class independent of the need for rigorous content. By having an LGBTQ lesson, you’re tokenizing our identity as opposed to normalizing our identity. Why, if you’re talking about quantum physics, and let’s just say an important person in that field happens to be LGBTQ, is it a bad thing to mention that in the context of their innovation? It might be interesting for people to know that. If you’re looking at biology for example, why can’t there be discussions about gender or intersex people, or the myth that XX and XY pairings are the only and there isn’t biological and chromosomal diversity beyond that? It’s just bad science. There are ways to talk about LGBTQ issues and ideas that are not tokenistic. Content and culture can enable strong learning and aren’t oppositional. We don’t have to say: “let’s take a break from our real work and talk about LGBTQ people”. I’d say the same thing about exposure to different cultures; it’s not helpful to say: “let’s talk about black people for 10 minutes”. What are the major roadblocks to LGBTQ+ education in schools? I think you have different generations of people that haven’t had the exposure. Often, what I find in schools is that it’s not predominantly students who are creating difficult challenges for queer and transgender kids, it’s the teachers who have been there forever who refuse to divorce their personal biases from their teaching. A good example of that is when I taught rhetoric at a conservative school in suburban Texas, and I had to help students write anti-gay marriage papers. Did I like to do that? No. But it was my job as a teacher to help them question their beliefs and, sometimes, help them craft as strong an argument as possible against something I felt strongly about. It’s not my job to convince my students to believe the way I do. It is my job to create a safe arena for the development and maturation of students’ opinions and thoughts. The role of a strong teacher in school is to create that setting and environment. Unfortunately, according to the data we see, LGBTQ students are not safe in high schools. They face a lot more harassment, they drop out at higher rates, truancy rates are higher, any number of indicators. How can non-LGBTQ+ teachers be good allies? I think one not to hypervisibilize LGBT students by treating them different that others, but to truly be committed to creating a classroom environment where ALL students feel like they have something to contribute to the class. Some of that is about intentionality and exposure. In your curriculum, is there something that can speak to the diverse background and experiences in class? Teachers who do that really well are really appreciated by students. It’s like, “oh wow — this is not just about the specific academic topic, but we’re also learning about ourselves and the people around us.” It’s important for student development. Otherwise, teachers should be good allies to queer and trans kids because it’s their job (that’s the smart-ass answer). It’s not about whether or not you want to support LGBTQ students. As a teacher, should be fully committed to the education of your students. Truly being committed means that you advance a classroom culture where anti-LGBTQ microagressions aren’t tolerated; where all students feel safe in your class and not harassed, because that can ultimately impact their ability to learn well. Students feeling safe to learn, or not, is a reflection on you as a teacher. Passing is the holy grail for many trans people, the almighty goal that they seek through the trials of transitioning. It is defined by the LGBT Resource Center at the University of Southern California as “successfully being perceived as a member of your preferred gender regardless of actual birth sex”, but the concept of passing is accompanied by controversy. It requires trans people to fit into a rigidly structured binary and fulfill gender stereotypes they may not wish to conform to, but it can also improve quality of life and keep them safe under circumstances where not passing would put them at risk. With both these arguments in mind, is the concept of passing helpful or harmful for the trans community? With regards to the earlier question, there is no clear answer. The concept of passing will remain controversial, and it is up to the individual whether or not they want to pursue it. Therefore, it’s important to remember that your perspective on passing does not hold true for everyone and that there are very distinct arguments on both sides. Like so many issues, it’s not a matter of black and white. Do what makes you feel the most comfortable, and respect the decisions of the people around you.

Have something to add to the conversation? Need some advice? Leave a comment below or tweet us at @LGBTQ_of_FIRST School can be a difficult environment for LGBTQ+ students. They can face problems like bullying, discrimination, and even not being allowed to use the right bathroom. There must be a way to help make their educational career easier. That’s what an ideal LGBTQ+ Movement Club would do. They would help wherever they can to make the school a safe space for people who are LGBTQ+ to be open and happy about who they are.

They would have to have ways of helping fellow LGBTQ+ students. Examples of assistance could be advocating for transgender students to be able to use their preferred bathroom or encouraging a culture of acceptance in their school for LGBTQ+ students. They could hold meetings for LGBTQ+ students to come talk to people that understand their life and what they go through. The meetings would be a safe place for them to come and be themselves, something they just may not have anywhere else. That’s ideally what a club like this would do. I think if every school had a club that did this, it would create a culture in not just the school but the community where LGBTQ+ students could be open about who they are without fear of prejudice and hate. They wouldn’t have to hide their orientation because of their fear of retaliation from their community. That would make any school and any community better. |

About LGBTQ+ of FIRST

LGBTQ+ of FIRST is a student run organization that advocates awareness and acceptance of LGBTQ+ students, mentors, and volunteers of FIRST Robotics. LGBTQ+ of FIRST reaches out to over 1000 members across the FIRST regions and fronts multiple outreach endeavors. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed